Here in Aotearoa, we take pride in doing things our way - whether it’s pioneering innovations, world-class rugby, or backyard ingenuity. But when it comes to building warmer, drier, healthier homes, there’s still room to grow.

We often see roofing systems that, while familiar, don’t always support the kind of long-term performance Kiwis need - especially as expectations (and our climate) continue to evolve. At Oculus, we believe every home should feel comfortable, be built to last, and perform well year-round.

That’s why we’re passionate about helping designers, builders, and homeowners make informed choices - starting with the roof. In this article, we’ll unpack why cold roofs are so common, the challenges they pose, and why a warm roof is the smart, science-led solution for future-ready homes.

Roofing in New Zealand Explained

The most common roof types in New Zealand are metal, membrane, and tile roofs (probably in that order). However, most people don’t always see the full picture of what’s happening within these systems, how they compare/contrast, and how the insulation and structure influence performance and durability.

We all know that insulating the ceiling keeps a home warm. While that’s true, it doesn’t tell the whole story. Once insulation is added, it keeps the interior warmer, but also changes how both temperature and moisture move through the building. That’s where the risk of interstitial condensation creeps in - particularly in the attic space.

There are only two typical ways to mitigate the risk of condensation in the attic space:

- Use a warm roof system fully outside the structure to keep all the surfaces in the attic above the dew point temperature

- Use a vapour control layer at the ceiling line, fully sealed around every penetration and junction to eliminate infiltration of relatively moist air from the interior into the attic, and provide a drainage cavity and sealed membrane behind the roofing

It’s commonly believed that providing adequate ventilation to the attic space will keep the attic dry, but there are studies from both Branz here at home and from the west coast of Canada that show this does not work in high humidity environments (common there and here in NZ), especially with high levels of ceiling insulation. Hygrothermal analysis for NZ-specific conditions confirms this as well.

Despite the above, the most common roof type in New Zealand is also the most problematic: a profiled metal cold roof without a vapour control layer.

Why Cold Roofs “Worked” - Until They Didn’t

Cold roof systems have been widely used across New Zealand for decades, largely because they’re simple, robust, easy to install, and used local materials as much of the metal roofing sheet in NZ is manufactured from ironsand ore turned into steel at the Glenbrook steel mill. Coils of sheet metal can be roll-formed on site to huge lengths and installed quickly with screws and flashings, so it’s no wonder it is the popular choice.

In the past, with no insulation and when most homes would have a fireplace running throughout the winter, heat would easily rise through the ceiling into the attic keeping it warm, and airflow would be pulled throughout the house to draw moisture and keep things dry. This helped prevent condensation, as warm air could absorb and carry away moisture.

That started to change 1977 when insulation became a requirement. This was a step forward for comfort as it keeps more of the heat inside, but it also keeps the surfaces within the attic colder. With a small amount of insulation, there’s still enough heat to keep things dry, but with higher R-values (such as the R6.6 schedule value introduced in the most recent H1 updates) the balance point tips and can interstitial condensation to form and build.

It also changed as fireplaces began to be replaced with heat pumps as the main form of heating. While heat pumps are much more efficient and eliminate the emission of smoke/particulates, they typically just recirculate interior air and do not exhaust moisture or provide ventilation with exterior air.

Some roofs can get lucky with the right annual mix of sun and prevailing winds to keep them dry for a long time even with thick ceiling insulation, but hoping for good luck is not proper design. Comprehensive design of a roof must ensure that it will work even if the sun and wind don’t cooperate.

When building today with higher levels of airtightness and insulation, higher expectations of comfort, and higher efficiency heating, it’s important to take a holistic approach, balancing:

- Exterior assemblies designed to avoid interstitial condensation

- Ventilation to maintain low CO2 (below 1000ppm) and manage indoor humidity (ideally between 40–60%)

- Heating throughout the space in all rooms to keep surface temperatures up

- Insulation to maintain comfort (ideally 18–25°C)

- Minimized thermal bridges

- Airtightness to reduce energy loss and prevent draughts

- Window design to manage light and heat gain/loss

And at the top of it all? Your roof - one of the most important elements of your entire building envelope.

The Comparison: Cold Roof vs Warm Roof

Let’s explore the key differences between cold and warm roof systems. This binary is a bit of a simplified way to look at a complex system, but it classifies all of the different roofing assemblies into those with the structure outside or infilled with the insulation versus those with the insulation fully covering the structure. Cold roofs have risk of condensation that needs to be addressed with additional components and detailing, whereas warm roofs tend to be simpler as the full roofing and insulation system is outside the structure.

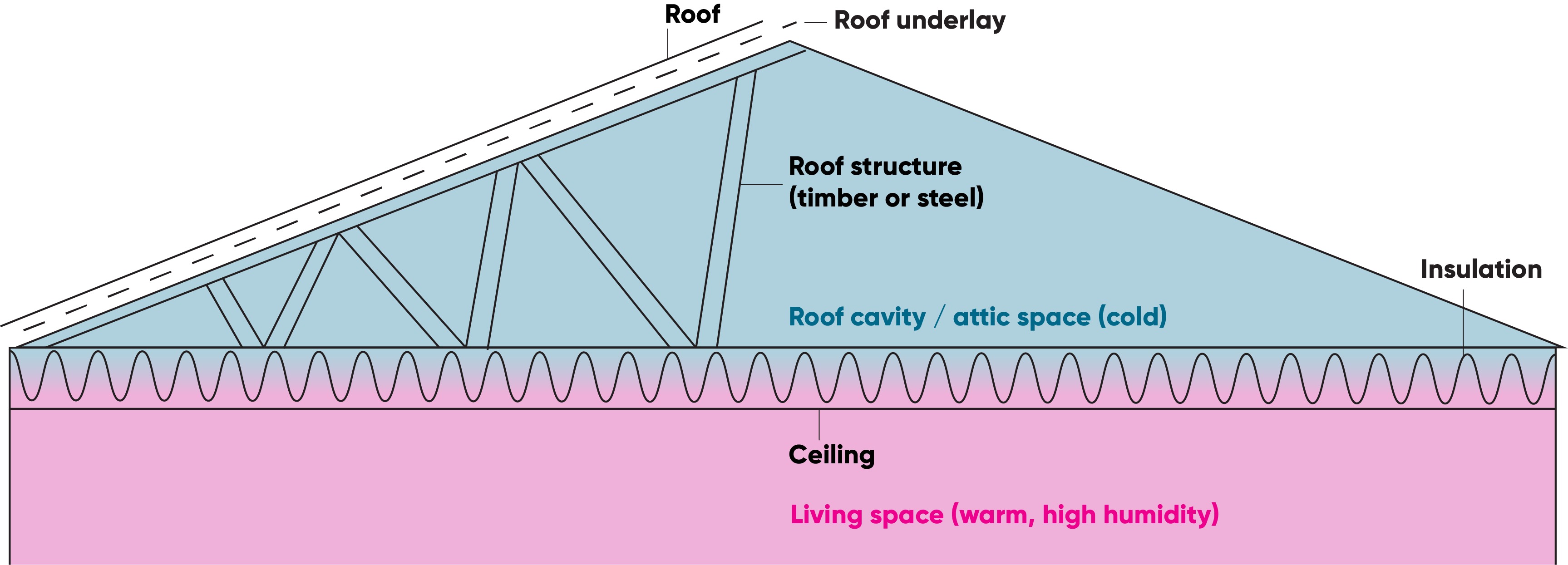

Cold Roof/Skillion roof

A cold roof places insulation at the ceiling line or within the rafters/beams in the case of a skillion roof. This keeps the living space warm, but the attic space remains cold and the structure within the attic or in the skillion roof will stay cold. It’s the most common system across New Zealand homes.

Two key challenges:

1. Water vapour rises and condenses on cold surfaces

Warm air holds high volumes of moisture, rises due to convection, and tries to make its way through penetrations such as lights, vents, etc. Moisture in the air can also make its way as vapour through the gypsum board and insulation into the attic space or skillion roof assembly. Because the attic and rafters are cold and the air is relatively warm and humid, water vapour from everyday activities (cooking, showering, breathing) rises and condenses on cold surfaces in the attic and on colder surfaces within the timber and insulation. Over time, this leads to mould, rot, and damage - especially in locations where there are many non-airtight ceiling penetrations like downlights and thick insulation above.

2. Night sky radiation and steel-framed roofs

On clear nights, radiative cooling can cause the roof temperature to drop below the air temperature, creating condensation as the metal surfaces radiate heat out into the darkness of space as infrared light. This is the same mechanism that causes dew and frost on nights where the air temperature is still above zero. Metal roofing is particularly prone to condensation on its underside within the attic space as the underside is regularly below the dew point temperature of the exterior air, so attic ventilation increases condensation rather than drying it. With typical E2/AS1 metal roof detailing, the underlay is shown hard up against the metal roof, which means it will be the same temperature as the metal and therefore will have condensation on its underside where it is uncontrolled.

This becomes an even bigger issue with steel framing as the metal roof above it acts as a heat sink keeping the steel framing cold, where condensation can form directly on the structure, dripping onto insulation and services, and accelerating mould and deterioration.

Even with ventilation, it’s difficult to dry out an attic filled with cold, damp air in winter, as the exterior air is cold and humid and cannot absorb more water unless it’s heated. This is unfortunately a system that while super common, has inherent condensation risk that will lead to durability issues prematurely down the road.

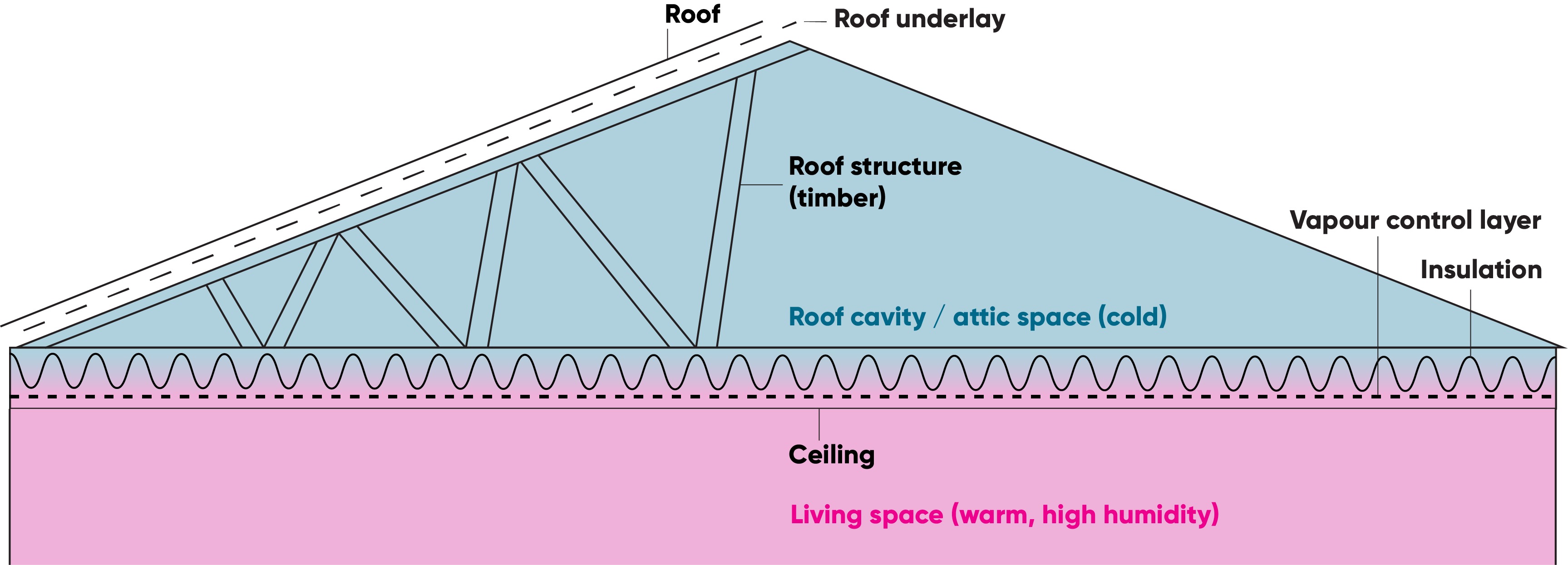

Cold Roof with Vapour Control Layer

This system adds a vapour control membrane (VCL) below the insulation at the ceiling line to prevent moisture from reaching the attic.

To be effective, the VCL must be completely sealed around downlights, services, and inter-tenancy walls. That’s easier said than done, and often comes with additional design and installation complexity, but may be the only option for certain designs.

To control condensation at the underside of the roofing, there needs to be a drainage cavity (min. 30mm) formed with ventilated metal battens or a lattice of timber battens over a watertight and airtight sealed membrane to protect the structure. This drainage layer also provides redundancy to the roofing system in case the roofing leaks. Lastly, the roof must have adequate pitch (above 15 deg) to promote stack effect in both the ventilation in the drainage cavity and attic.

At Oculus, we’ll only approve this system for use where the roof framing is timber, as it’s less conductive than steel and can absorb and release small amounts of moisture over time. Any exterior assemblies using steel framing should have a warm roof/exterior insulation.

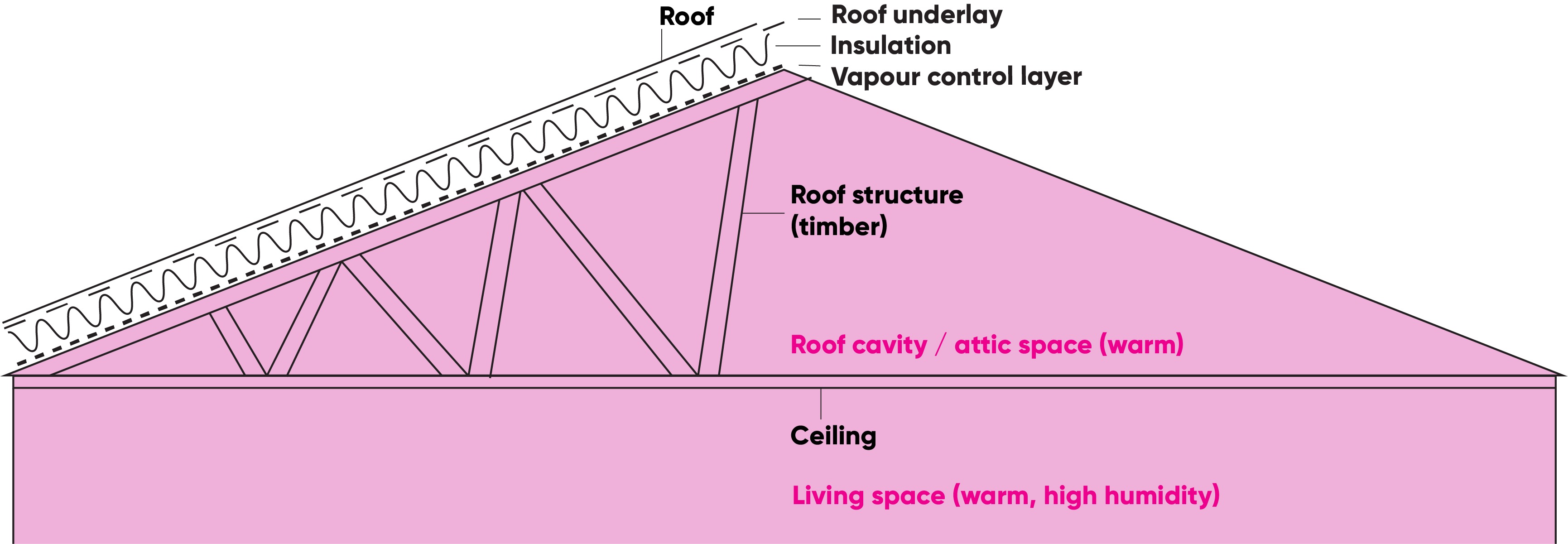

Warm Roof

A warm roof moves the insulation layer outside the roof structure, keeping the attic space and structure (timber, steel, concrete, or whatever else) warm. This prevents the daily temperature swings and cold surface temperatures that cause condensation.

In this system, the attic becomes part of the interior environment, meaning:

- No need for a VCL or additional detailing at the ceiling line

- No risk of condensation on structural elements

- No windwashing of insulation through attic vents

- No interstitial moisture to manage

- Stable, healthy interior temperatures and humidities for plant/mechanicals/storage

It’s a simple, high-performing system that addresses both temperature and moisture from the start without relying on complicated workarounds.

Warm roofs come in many different flavours including those with:

- metal roofing

- different membrane materials

- different insulation materials

- protected membrane roofs which have insulation outside a membrane and covered by ballast.

- Structurally insulated panels that include or exclude the exterior roofing

But the key factor is that the insulation line is fully outside the structure.

"Aren’t Warm Roofs Too Expensive?"

That’s one of the most common questions we get, as they are not the most typical type of roof, but they’re not typically compared apples to apples. A warm roof assembly would obviously be more expensive than just a sheet of metal and underlay, but it provides benefits that reduce costs in other ways, which could ultimately save money. When comparing costs, you must include:

- Deleting the ceiling/attic insulation

- Gaining storage space/plant space without additional structure

- Avoiding the need for a ceiling VCL or special detailing

- Avoiding the need to slope the structure (if using sloped insulation)

- Avoiding the need to have monoslopes and box gutters by sloping direct to drain with sloped insulation under a membrane)

- Allowing for zero slope roofs (if using monolithic protected membrane)

- Adding redundancy, as warm roofs typically have an external roofing surface and an internal vapour barrier membrane.

- Avoiding future repair/maintenance costs due to durability issues from condensation.

The real cost isn’t the warm roof, it’s everything you have to add to a cold roof to make it work.

When designed correctly, warm roofs can:

- Be more cost-effective than a cold roof once you factor in extra membranes, ventilation, and detailing

- Improve long-term energy performance due to reduced thermal bridges

- Deliver healthier living conditions by avoiding interstitial condensation and providing additional leak redundancy

- Reduce risk for designers and builders

The upfront investment pays off with less maintenance, fewer surprises, and better outcomes for everyone involved.

The Data Doesn’t Lie: Why Cold Roofs Fail Over Time

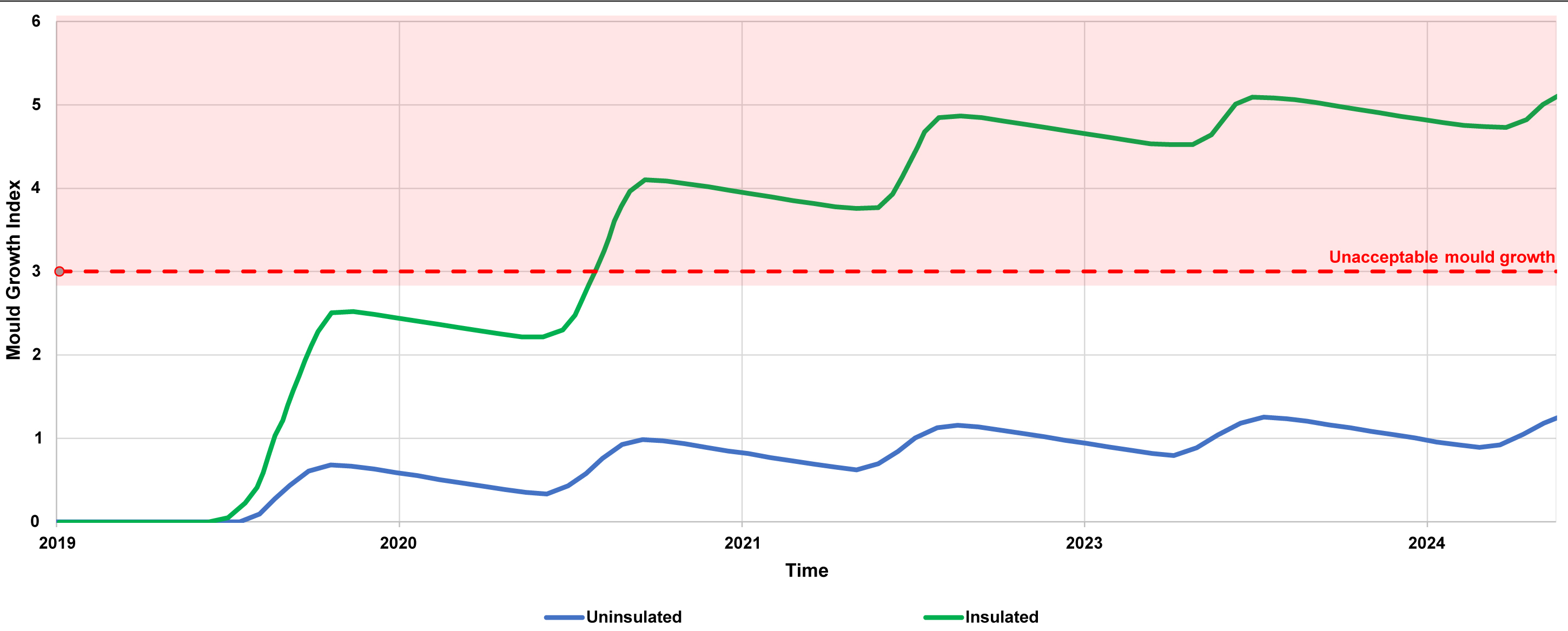

Research shows that old, uninsulated or lightly insulated cold roofs didn’t accumulate mould because the attic stayed warm enough year-round due to the low ceiling R-value

But as soon as more ceiling insulation is added without air/moisture control, mould can start growing and build over time. In fact, the data shows that mould levels can exceed acceptable thresholds within just 18 months.

It’s a powerful reminder that adding insulation isn’t enough. You must also understand how heat, airflow and moisture interact within your roof assembly.

Tired of Designing Around Risk and Uncertainty?

We hear it all the time - navigating building code complexity, moisture management, and performance requirements can feel like a juggling act. When it comes to roofs, the stakes are even higher. Get it wrong, and you’re dealing with long-term liability, rework, or worse - unhealthy homes.

That’s where we come in.

We partner with architects, designers and project leaders to simplify complexity and design high-performing enclosures - roofs included. Because we don’t just focus on façades. Our team brings deep expertise across the whole building envelope, including the less familiar code clauses like C3, E3, G4 and H1.

We work alongside you from concept to construction to:

- De-risk your design with science-backed solutions

- Simplify consent with clear pathways

- Improve detailing for buildability

- And support smarter decision-making with every step

You don’t need to navigate it all alone. With the right partner, designing for performance doesn’t have to mean compromise or confusion - it can mean clarity, confidence, and buildings built to last.

Planning a warm roof? Or wondering if a cold roof can cut it?

We’ve helped dozens of teams find the right roof solution for their project and avoid the common traps that lead to costly surprises later. If you're weighing up your options, let’s talk early and get it right from the start.

Email us at info@obsf.co speak to the team directly.

References:

- BRANZ SR289 – Remediating Condensation Problems in Large-Cavity, Steel- Framed Institutional Roofs 2013

- BRANZ SR343 – Numerical Simulation Of Ventilation In Roof Cavities, 2016

- BRANZ Discussion Document – Initial Guidance on the Moisture Design of Large-Span Roofs for Schools - 31 March 2015

- BRANZ Build 151 – Roof Space Moisture - 01 December 2015

- BRANZ SR 228 Condensation Resistance of Roof Underlays

- BRANZ Roof Ventilation Articles 1-4

- BRANZ SR401 - Airtightness of Roof Cavities

- BRANZ Bulletin 630

- RDH – State of the art review of unvented sloped wood framed roofs in cold climates

- MRM Ventilation of attic spaces

- BRANZ - Keeping your home warm and dry

- Niwa